BREEDING YOUR FROGS

What is your Goal breeding frogs?

Breeding frogs can be an exciting event. To watch the translucent eggs

develop into tadpoles is amazing. The morphing of tadpoles

into froglets and finally into adults is

something you don't soon forget. And the neatest thing of all, is

that you have a hand in the entire event!

Breeding frogs can be an exciting event. To watch the translucent eggs

develop into tadpoles is amazing. The morphing of tadpoles

into froglets and finally into adults is

something you don't soon forget. And the neatest thing of all, is

that you have a hand in the entire event!

But you must ask yourself,"why do I want to do this?" Are you ready for all of the intense work that will go into a successful frog colony breeding? Do you have the short but close intervals of time necessary to pull this off? Are you dedicated and knowledgable enough to begin? You are experienced in keeping the species alive and happy for a year or so already? Do you have future homes or other destinations (selling some to the local pet herp shop, for example) lined up for the many morphlings? Ask yourself these questions before breeding frogs.

More money will go into this endeavor than many

may think. And monentary gains should be the last thing you're thinking, as most small time breeders never begin to break even.

A rainchamber, nursery tanks, water conditioners, filters, pumps,

lighting, heating, tiny insects,

morph tanks, and many other items will cost the breeder an

extensive amount of cash right from the beginning. Most small timers are doing it for one or two reasons only. For love of the species, and the knowledge and excitement of of possibly succeeding. Some of the more advanced Froggers may have the intention of trying to save a threatened species of frogs.

More money will go into this endeavor than many

may think. And monentary gains should be the last thing you're thinking, as most small time breeders never begin to break even.

A rainchamber, nursery tanks, water conditioners, filters, pumps,

lighting, heating, tiny insects,

morph tanks, and many other items will cost the breeder an

extensive amount of cash right from the beginning. Most small timers are doing it for one or two reasons only. For love of the species, and the knowledge and excitement of of possibly succeeding. Some of the more advanced Froggers may have the intention of trying to save a threatened species of frogs.

Frog colonies meant for breeding purposes will demand many things from you in order to reproduce. The ecosystem you set up for them must replicate their natural environment as closely as possible, giving them every advantage and bringing you closer to success. Other factors include the right humidity, rain, warmth, stress, and size of Vivarium and food resources. Controlling these factors is called cycling, which we'll talk more about later.

Misting Systems

A Misting routine or system is crucial for breeding your colony of frogs.

Misting Systems can be as complicated

as being set up on timers, to as simple as you spraying the prepared tank. You will need

to supply the effect of heavy rains in a

Rainchamber (sometimes called a breeding

chamber) so if you're serious about

breeding your frogs, this would be the way to go.

A Misting routine or system is crucial for breeding your colony of frogs.

Misting Systems can be as complicated

as being set up on timers, to as simple as you spraying the prepared tank. You will need

to supply the effect of heavy rains in a

Rainchamber (sometimes called a breeding

chamber) so if you're serious about

breeding your frogs, this would be the way to go.

On the Rainchamber page, is a description of how to build your own misting/rain system.

Building your own Rain chamber is only a bit complicated, but a must to breed frogs. You can find out how to build your own on the Rain Chamber Page.

Tank Size does Matter

As mentioned on the page Vivarium, you should set up the largest vivarium or aquarium that you can afford. Small pipids, such as the dwarf clawed frogs, will breed in a 20 gallon aquarium. Larger pipids like Xenopus Laevis require a 55 gallon tank and up. If you're trying to breed a frog as big as the African bullfrog, I suggest at least 125 gallon tank that is longer and wider than it is high. If I'm breeding Red-eyed treefrogs, I require no less than a 55 gallon tank that is tall and planted lushly.

Also knowing the climate your frog is originally from will go a long way in assisting

you with the main vivarium, "rainfall" and temperature you will need to try to duplicate.

Read through the  World climates listed further below, then find your frog species. There you will find information to help optimize a particular climate vivarium.

World climates listed further below, then find your frog species. There you will find information to help optimize a particular climate vivarium.

The Breeding Colony

Frog Species that live from 6-up years and will be used in the breeding colony

should be anywhere from 2 to 3 years old. This insures sexual maturity. Many

species longevity records are listed on the

Frog caresheets page.

Frog Species that live from 6-up years and will be used in the breeding colony

should be anywhere from 2 to 3 years old. This insures sexual maturity. Many

species longevity records are listed on the

Frog caresheets page.

A larger population of males is also recommended. This promotes the ideal that they will compete for the females' attention. A good ratio would be 2 or 3 males to every one female. It is not always easy to sex all frog species. If you have a colony of frogs that are not easy to sex, having a population of 7 to 10 frogs should insure that you have enough males to females. Certainly Froggers have succeeded with less numbers, but the more you have the more excited the males become, promoting the idea of propagation of the species.

Note that too much disturbance on your part can result in frightening the frogs. This can cause the males to leave many eggs unfertilized. If you really must "see", try a red light in one corner of the rainchamber. Then sit very quietly and still in place. The red light will not disturb the nocturnal breeders, and you will be able to observe them.

Sexing Frogs

In most species, the female is larger, but this cannot be a

guarantee...nor the song. Females will chirp if frightened, agitated, or otherwise

annoyed. Wait until your colony is of age, listen and watch, and you should have a

better idea of what and how many of each sex you have.

Since the males are the long time singers, watching them after the

brumation

or aestivation

process is finished, you can see how many males to females

you really have. I play looped tapes of their species to them, and then watch and listen for the males in the vivarium to chime in. Then I can directly identify my males from my females.

In most species, the female is larger, but this cannot be a

guarantee...nor the song. Females will chirp if frightened, agitated, or otherwise

annoyed. Wait until your colony is of age, listen and watch, and you should have a

better idea of what and how many of each sex you have.

Since the males are the long time singers, watching them after the

brumation

or aestivation

process is finished, you can see how many males to females

you really have. I play looped tapes of their species to them, and then watch and listen for the males in the vivarium to chime in. Then I can directly identify my males from my females.

Females that are always larger include Xenopus pipids, Red-Eyed treefrogs, and many other species of frogs you find in the Herp trade today. In American Bullfrogs and the American Green frog; the males develop a deep yellow throat, and the thumbs of each hand turn inward, like "hooks". This is so they can grasp the females when in amplexsus. Their grasping fingers can also turn the same yellow color found on their throats. This also happens to many other male species as they reach the breeding season.

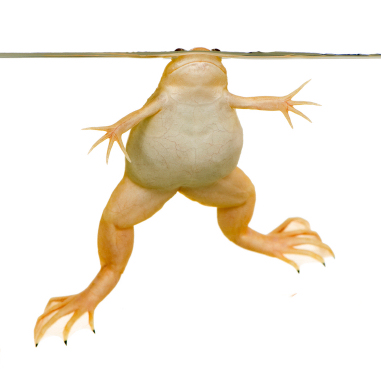

Breeding Xenopus Frogs

African Clawed frogs should be a at least two years old

before attempting to breed them.

Females are easy to distinguish from males, as they will grow much

larger

than the male, and have a skin attachment similar to a flower bud for

their cloaca. The males are thinner as well as smaller, and have a

different body shape, leaner and longer in appearance. The males are

kind of pear-like in silhouette.

African Clawed frogs should be a at least two years old

before attempting to breed them.

Females are easy to distinguish from males, as they will grow much

larger

than the male, and have a skin attachment similar to a flower bud for

their cloaca. The males are thinner as well as smaller, and have a

different body shape, leaner and longer in appearance. The males are

kind of pear-like in silhouette.

These fully aquatic frogs are wonderful for classrooms and easy to care for. Students can easily partake in their care, and will love the acrobatic, comical look to these frogs. Just remember to never release into the wild! To learn more and purchase this frog, try this link: LivingAquatic

Before going any further in this section, read  The top of Breeding Cycles and paragraph

The top of Breeding Cycles and paragraph .

Then read the following:

.

Then read the following:

Now you can start to mock the

aestivation process.

Do this part of the process for about 70 days.

Lower the level

of the water to

about 6" in their main tank. Make sure they

still have access to "caves" and other hiding places.

Quit feeding the frogs entirely,

and let the tank cool to between 65 ° and 70 °. Keep undergravels

and any sponge filters with heads still underwater working. To ensure

that the undergravels keep functioning, change the clear plastic

pipes to ones short enough to allow water flow back into tank.

Make sure they have rocks and caves to hide in during this time. I also

cover the tank with a piece of loosely woven white canvas, and

disturb them only every other day during this time, to replace any

evaporated water and remove any frog that does'nt make it through.

After the cycle is completed, you can now feed the frogs a few bugs

each night, working up to

their regular food intake within two weeks. Add calcium supplements

to the female's meals. Over a one week period, raise the temperature

levels back to normal. Make sure the females are quite fat and

should appear ripe with eggs before the next step. After females

look ready, place both frog sexes into an aquatic style rainchamber

you have

prepared.

After the cycle is completed, you can now feed the frogs a few bugs

each night, working up to

their regular food intake within two weeks. Add calcium supplements

to the female's meals. Over a one week period, raise the temperature

levels back to normal. Make sure the females are quite fat and

should appear ripe with eggs before the next step. After females

look ready, place both frog sexes into an aquatic style rainchamber

you have

prepared.

In the rainchamber, raise water level to between 8" and 12". Have the water in chamber at 75 ° to 78 °. Having two or three males is also advised. Placing some short plastic plants or some rocks (not gravel-sized) in the chamber will give the females somewhere to lay their eggs. Females can lay 500 to 2000 eggs at one time.

If all has gone well, you should be able to hear the male frogs croaking after

you turn the lights off at night. (yes, they croak under water!) Keep a close eye on the rain chamber now,

as African clawed frogs have been known to eat the eggs. You will need to remove them and

place them back into their tank as soon as you see the egg masses. Remove the eggmasses, divide into small groups and place

into tadpole nursery tanks. The page

Tadpole Care will help you in tadpole tanks and rearing. Be sure to see the special section on rearing xeno tadpoles. They are  filter feeders and eat

quite differently than most tadpoles.

filter feeders and eat

quite differently than most tadpoles.

World Climates

Below is a list of different climates that your frog may be from. It is a

good idea to become familiar with the frogs' homeland environment,

especially if you want to breed them. Duplicating it as closely as possible can aid in breeding your

colony later on. I will list some frogs living there, and some plants native to that climate.

Below is a list of different climates that your frog may be from. It is a

good idea to become familiar with the frogs' homeland environment,

especially if you want to breed them. Duplicating it as closely as possible can aid in breeding your

colony later on. I will list some frogs living there, and some plants native to that climate.

If you see some species listed in more than one climate, it is because this frog is a sub-species and/or has learned to live in more than one environment.

Climates of the world depend upon their global location in relation to the equator, what properties lie next to them (i.e. The Atlantic, Pacific, a mountain range, etc.) and their elevation. Frogs live in all types of environments and climates, and all continents except the Antarctica. Finding out more about the climate your frogs are from will help you in the "cycling" process and to set up the best vivarium that you can.

Rainforests

There are rainforests throughout the world, and not just the tropical ones that most people think of. As an example, there is a cool temperate rainforest on the coast of southern Alaska! The rainforests furthest from the equator can have 2 wet and 2 dry seasons, for a total of 4 seasons.

There are rainforests throughout the world, and not just the tropical ones that most people think of. As an example, there is a cool temperate rainforest on the coast of southern Alaska! The rainforests furthest from the equator can have 2 wet and 2 dry seasons, for a total of 4 seasons.

Rainforests closer to the equator experience no seasons, where it usually rains

year round, and a monsoonal condition exists, in which it will rain more than it

usually does during that time. Humidity in a typical rainforest is about 80%.

Frogs commonly seen for sale from this environment include the

Red-eyed Treefrogs, Gliders like Rhacophorus reinwardtii,

Red-eyed Treefrogs, Gliders like Rhacophorus reinwardtii,

Asian brown treetoads,

Madagascars' Tomato frog, the

Ornate horned frogs and the

Northern dwarf tree frog.

Other less common species living in this climate

include

Giant treefrog,

Asian brown treetoads,

Madagascars' Tomato frog, the

Ornate horned frogs and the

Northern dwarf tree frog.

Other less common species living in this climate

include

Giant treefrog,

Giant South-American Gladiator frog,

the

Giant South-American Gladiator frog,

the  Cashew frog

and the Australian Lacelid.

Cashew frog

and the Australian Lacelid.

Plants commonly found in these regions include Alocasia, Elephant ear,

cynoches orchids,

cynoches orchids,

bromeliads and

bromeliads and

heliconia.

heliconia.

Cloud Forests

Cloud forests usually do not receive much rain. However, they do receive

sufficient moisture through the constant mist of the clouds. It is a cooler,

higher elevation.

Cloud forests usually do not receive much rain. However, they do receive

sufficient moisture through the constant mist of the clouds. It is a cooler,

higher elevation.

Typically temperatures at these elevations drop 30 degrees lower at night

than they were in the day. Standard vivarium temperatures for this set-up

would be between 68 ° and 75 °. Going over 75 ° can cause

undue stress. Setting up a

fogger for this type of vivarium is also a plus, helping to make the frogs feel more at home.

fogger for this type of vivarium is also a plus, helping to make the frogs feel more at home.

Plants for the vivarium from cloud forests would include

bromeliads and

other epiphytes such as

bromeliads and

other epiphytes such as

orchids. Frogs from the cloud forests include many

species of Dendrobates, Leptodactylus, Eleutherodactylus, Epipedobates, Mantellas and Colosthethus.

orchids. Frogs from the cloud forests include many

species of Dendrobates, Leptodactylus, Eleutherodactylus, Epipedobates, Mantellas and Colosthethus.

The Temperate Forests

There are four types of temperate forests in the world. Deciduous, Evergreen,

Temperate Rain forest, and Mixed Deciduous & Evergreen. The temperate rain forest

maintains an average temperature of 60 °. The other 3 receive change in

temperature with each of the four seasons. North America is mostly a temperate

and cool temperate climate, although the deep south such as Florida, and places

like the south-west tip of Texas and the city of San Diego are considered sub-tropic.

The average humidity in a temperate forest is 60% to 80%. Plants for your vivarium from the

cool temperate forests include

There are four types of temperate forests in the world. Deciduous, Evergreen,

Temperate Rain forest, and Mixed Deciduous & Evergreen. The temperate rain forest

maintains an average temperature of 60 °. The other 3 receive change in

temperature with each of the four seasons. North America is mostly a temperate

and cool temperate climate, although the deep south such as Florida, and places

like the south-west tip of Texas and the city of San Diego are considered sub-tropic.

The average humidity in a temperate forest is 60% to 80%. Plants for your vivarium from the

cool temperate forests include

sellaginella fern,

live sphagnum moss, cat-tail moss (isothecium myosuroides)

deer fern, sword fern, hellborne and trillium. (careful, trillium is poisonous,

will not hurt frogs but protect children) Temperate Forest frogs include

sellaginella fern,

live sphagnum moss, cat-tail moss (isothecium myosuroides)

deer fern, sword fern, hellborne and trillium. (careful, trillium is poisonous,

will not hurt frogs but protect children) Temperate Forest frogs include

the bombinas, or fire-bellied toads,

Rana sylvatica,

Australian marsupial frog,

Fletchers' frog from Venezuela, the

the bombinas, or fire-bellied toads,

Rana sylvatica,

Australian marsupial frog,

Fletchers' frog from Venezuela, the

Green treefrog,

Green treefrog,

Springpeeper,

Emerald spotted treefrog,

Laughing treefrog,

Pine Woods treefrog, and some

frogs that live in both England and America, the species Rana lessonae,

Springpeeper,

Emerald spotted treefrog,

Laughing treefrog,

Pine Woods treefrog, and some

frogs that live in both England and America, the species Rana lessonae,

Rana clamitans,

Rana temporaia and

Rana clamitans,

Rana temporaia and  Bufo bufo ; the last of which is a toad.

Bufo bufo ; the last of which is a toad.

Sub-Tropical Climates

Several places in the United States are lucky

enough to languish through a sub-tropical climate instead of the cold northern

winters! These climates

usually enjoy just 2 seasons, spring and summer. Rainfall

in these areas are about 65 to 85 inches a year, and sub-tropical plants abound everywhere.

Humidity is high too, about 60 % to 100 %. Temperature in 'spring'

(the coldest time of year & occurs in late 'fall-winter' time for rest of country)

rarely drops below 40 ° . The relative humidity drops at this time also, to around

20% to 40%.

Several places in the United States are lucky

enough to languish through a sub-tropical climate instead of the cold northern

winters! These climates

usually enjoy just 2 seasons, spring and summer. Rainfall

in these areas are about 65 to 85 inches a year, and sub-tropical plants abound everywhere.

Humidity is high too, about 60 % to 100 %. Temperature in 'spring'

(the coldest time of year & occurs in late 'fall-winter' time for rest of country)

rarely drops below 40 ° . The relative humidity drops at this time also, to around

20% to 40%.

Good vivarium plants include bird's nest ferns,

orchids,

orchids,

bromeliads

and oyster bush. Philodendrons like

bromeliads

and oyster bush. Philodendrons like

Monstera deliciousa, spathiphyllum,

and

Monstera deliciousa, spathiphyllum,

and

spathos vine

work well also.

spathos vine

work well also.

Frogs native to this climate include the

Pine barrens treefrog,

Pine barrens treefrog,

Cuban treefrog, the

Squirrel treefrog, the little

Grass frog, Southern chorus frog,

Cuban treefrog, the

Squirrel treefrog, the little

Grass frog, Southern chorus frog,

Southern toad,

Greenhouse frog,

Southern toad,

Greenhouse frog,

Giant Marine toad

and the Pig frog.

Giant Marine toad

and the Pig frog.

Asian climates are tropical in nature. If you keep rhacophorus species, try this link: Asian Climates

Savanna Climates

Savanna climates usually appear between rainforests and deserts. Most vegetation consists of tropical grasses and scattered trees. During all months the average temperature is above 64 °.

Savanna frogs and toads are found over a wide array of landscapes, from open grasslands to thick underbrush filled with many trees and shrubs. Savannas also experience a great fluctuation in humidity and temperatures. They typically have a very low humidity and high temperatures in daylight hours, and this is throughout most of the year, even during dry spells in the rainy season. At this time however, the forest areas will have a more stable, cooler humid microclimate than the surrounding grassland.

As mentioned above, savannas experience wet and dry seasons. There are dramatic changes between these seasons too. Without the rains of the wet season, the grasses die and the trees lose their leaves. Fires start from lightning. The wet season restores the green, the pools and the ponds. East Africa, much of Brazil (yes, Brazil) inland India, Indo-China and northern Australia are examples of places offering up the savanna climate.

The landscape also varies depending upon the location. Some frogs listed

in savanna climates actually live within the tree-range, which supplies

more moisture as well as shelter than the actual open savanna grasslands.

The landscape also varies depending upon the location. Some frogs listed

in savanna climates actually live within the tree-range, which supplies

more moisture as well as shelter than the actual open savanna grasslands.

The frogs will stay near a permanent water source if at all possible.

Plants native to savanna climate structure include those of the

'Euphorbia'

family(very unusual African plants) Hibiscus asper,

'Euphorbia'

family(very unusual African plants) Hibiscus asper,

Nile lettuce,

Nile lettuce,

'Cyperus papyrus'.

Amphibians indigenous to this type of climate include the

'Cyperus papyrus'.

Amphibians indigenous to this type of climate include the

South-African

painted reed frog and the other species of reed frogs,

South-African

painted reed frog and the other species of reed frogs,

green toad and the

green toad and the

the red-legged running frog.

In the Americas, the Northern leopard frog,

the red-legged running frog.

In the Americas, the Northern leopard frog,

Copes'

gray treefrog,

Pacific treefrog,

the Spotted chorus frog, the colorado river toad and the north west American

Great Basin spadefoot toad. Some more African frogs include Bufo hoeschi

or the Okahandja toad, Bufo grandisonae, the Mossamedes toad and Bufo boreas

halophilus. In South America, Monkey frogs like the

Waxy Monkey treefrog,

Tiger-leg Monkey frog live in savannah climates. The Asian Mali screeching frog also lives in the savanna

climate-range.

Copes'

gray treefrog,

Pacific treefrog,

the Spotted chorus frog, the colorado river toad and the north west American

Great Basin spadefoot toad. Some more African frogs include Bufo hoeschi

or the Okahandja toad, Bufo grandisonae, the Mossamedes toad and Bufo boreas

halophilus. In South America, Monkey frogs like the

Waxy Monkey treefrog,

Tiger-leg Monkey frog live in savannah climates. The Asian Mali screeching frog also lives in the savanna

climate-range.

The page Planting Vivariums has many other plants suitable for savanna vivariums and their care described for you.

The Steppe Climates

The Steppes of Russia and the Great plains of the United States are examples of

this climate. They both enjoy four seasons, and most of the precipitation is in the winter months, when its' also cooler of course.

The temperatures vary greatly between seasons.

The Steppes of Russia and the Great plains of the United States are examples of

this climate. They both enjoy four seasons, and most of the precipitation is in the winter months, when its' also cooler of course.

The temperatures vary greatly between seasons.

Some plants common to these

areas include different species of Dianthus, Campanula, Galium, Salvia,

Gasteria,

Gasteria,

Verrucosa

and Thymus.

Verrucosa

and Thymus.

Frogs and toads living in this environment are Triturus

vittatus,

green toad,

Bufo calamita, Pelodytes caucasicus, Rana esculenta,

Rana ridibunda, Rana lessonae, and some species of

Grass frogs.

green toad,

Bufo calamita, Pelodytes caucasicus, Rana esculenta,

Rana ridibunda, Rana lessonae, and some species of

Grass frogs.

Desert Climates

Places in the world with desert climates include the Southwestern regions of the United States, Sahel of Africa, Iran, Iraq, Nambia, Africa and Australias' interior.

The average rainfall in these areas is less than 2" a year. Any frogs you have from these areas will most likely stay buried deep in burrows, where the humidity is at its' highest. He may come up in the evenings to eat, after the scalding sun has set. When the rains of spring finally appear, up he'll come, mate and then return to the bowels of the earth. Toads are more common in this climate, but some frogs may be found where there is an Oasis or a canyon stream.

Desert plants for the vivarium would include

succulents like Aloe vera, and

Lithops.

(you'll like them, they look

like tiny pebbles)

Lithops.

(you'll like them, they look

like tiny pebbles)

![]() Ceropegia

and

Ceropegia

and

Euphorbia

works well too.

Euphorbia

works well too.

Amphibians living in this climate include the

Boreal chorus frog,

the Great plains toad, the

Amphibians living in this climate include the

Boreal chorus frog,

the Great plains toad, the

Canyon

treefrog,

Hyla arenicolor, Arizona toad,

the Colorado River toad the Green toad, the

Canyon

treefrog,

Hyla arenicolor, Arizona toad,

the Colorado River toad the Green toad, the

Cliff chirping frog, and the

Spadefoot toad.

Cliff chirping frog, and the

Spadefoot toad.

Cool Temperate Climate

Places like New England in the United States, the British Isles, Northwestern Europe, New Zealand, the Pacific Northwest United States and British Columbia of Canada share this climate. They have four distinct seasons, with moisture of some sort during all of them.

The frogs living in this climate will breed in spring and hibernate (in nature) for winter. They'd have a cool beginning in spring, with drenching rains and summer storms. In fall the rains would lessen as the weather cooled, and then finally the snows of winter, when frogs would be deep underground, sleeping away until the next spring.

Frogs from this climate include the American bullfrog,

the

Green frog, springpeepers,

Pickerel frogs, the

Eastern Spadefoot toad, Northern leopard frog,

Mink frog,

Green frog, springpeepers,

Pickerel frogs, the

Eastern Spadefoot toad, Northern leopard frog,

Mink frog,

Wood frog,

Wood frog,

Pine barrens treefrog and

Pine barrens treefrog and

Copes gray treefrog.

Copes gray treefrog.

Plants suitable for this vivarium include the

Spiderplants,

Spiderplants,

Sanservia,

Sanservia,

certain ferns

and for a ground cover, you can use

certain ferns

and for a ground cover, you can use

Dichondra or

Dichondra or

live moss.

live moss.

Wet & Dry Seasons

In South America, the wet season varies. Costa Rica has a drier season November through May. During this time, it still showers in the afternoons. Wet season is typically June through November, and it rains everyday for several hours.

In the Queensland Australian rainforest, the wet season is November through January. In the Galapagos and Ecuador region, dry season is June or July through November. Wet season is December through May.

This is of import to you if you're keeping Aussies, (as I call them) or Litoria carulea∼otherwise known as the dumpy treefrog, whites treefrog, etc.

Back to Costa Rica. Temperatures are between 80° and 95° at the lower elevations. In the higher elevations, they drop 30° from the daytime temps. The Galapagos and Ecuador climates enjoy temperatures of 74-78° in the dry season, and 80-86° in the wet season. Rainfalls here are 1/2" to 1" monthly during the wet season.

The lovely

Agalchnis callidryas (Red-eyed treefrog) is from Costa Rica.

Agalchnis callidryas (Red-eyed treefrog) is from Costa Rica.

Cycling your frog colony

Preparing your frog colony for a cycling process is very important.

All the frogs should be healthy, of age enough to breed, disease free

and genetically diverse.

Preparing your frog colony for a cycling process is very important.

All the frogs should be healthy, of age enough to breed, disease free

and genetically diverse.

Any frogs that you have doubts about their age and health conditions, I personally would not use in the cycling process.

First fatten up the frogs

through extensive feeding and the warming of their vivarium before

putting them through the grueling (sometimes deadly) task of cycling.

Feed both the males and the females as much as they can eat

without popping, keeping tank at it's optimum temperature range. Do this

for 6 weeks before moving onto the cycling process.

First fatten up the frogs

through extensive feeding and the warming of their vivarium before

putting them through the grueling (sometimes deadly) task of cycling.

Feed both the males and the females as much as they can eat

without popping, keeping tank at it's optimum temperature range. Do this

for 6 weeks before moving onto the cycling process.

For a special table on cycling and breeding frogs from various climates,Click Here.

Now you can start the

brumation stage. Use the

Breeding table to pick

the amount of time needed for this.

Quit feeding the frogs entirely, and depending upon the species natural global location,

let the tank cool to between

temperatures listed in table below.

Hideouts and tree holes should have dampened moss placed in them. Keep

this moss damp throughout the brumation time, checking it every

other day as you check on the frogs. Leave any filters running that you

have placed in their pool(s). Lower the water level in the pools,

but don't ever let them get dirty or go dry. No misting or fogging

of vivarium now.

Now you can start the

brumation stage. Use the

Breeding table to pick

the amount of time needed for this.

Quit feeding the frogs entirely, and depending upon the species natural global location,

let the tank cool to between

temperatures listed in table below.

Hideouts and tree holes should have dampened moss placed in them. Keep

this moss damp throughout the brumation time, checking it every

other day as you check on the frogs. Leave any filters running that you

have placed in their pool(s). Lower the water level in the pools,

but don't ever let them get dirty or go dry. No misting or fogging

of vivarium now.

I also cover the tank with a piece of loosely woven white canvas, (monk's cloth) and disturb them only every other day during this time, to replace any evaporated water and remove any frog that does'nt make it through.

After the

aestivation,

or brumation cycle is through, separate the sexes and place

in different tanks. Feed all the frogs a few bugs each night, working

up to their regular food intake within two weeks.

Add calcium supplements to the female's meals. Over a one week period,

raise the temperature levels back to normal. Make sure the females

are quite fat and should appear ripe with eggs before the next step.

After females look ready, place both frog sexes into the rainchamber

you have prepared.

After the

aestivation,

or brumation cycle is through, separate the sexes and place

in different tanks. Feed all the frogs a few bugs each night, working

up to their regular food intake within two weeks.

Add calcium supplements to the female's meals. Over a one week period,

raise the temperature levels back to normal. Make sure the females

are quite fat and should appear ripe with eggs before the next step.

After females look ready, place both frog sexes into the rainchamber

you have prepared.

Depending upon the type of frog you're breeding, the rainchamber will vary. Leaf rollers lay their eggs above the water level, so need a rainchamber that is heavily stocked with pothos or dwarf banana leaves around the pools edges. Frogs laying their eggs directly in the water need a larger aquatic area than the leaf layers. Still others, like dendrobates and mantellas, will need either bromeliad cups or loose leaf litter on the chamber's floor in order to lay their eggs.

Whether or not you've already built your rainchamber, or even bought one, you still need to read through the rainchamber's page menu to note other topics of breeding interest and care of the eggs. After that, move on to the Tadpole care page.

Read other breeder's sheets about your particular species. I have placed links to some exciting and educational sites here for further help to you. They are just below the table. Good luck!

*For Desert climates, use the information for Savanna climate.

Breeding other Species

If Dwarf pipids are your cup of tea, visit a website created by Brandon Ballengee, who is currently trying to breed/preserve

a pure strain of Hymenochirus curtipes (1 of 2 dwarf pipid species offered in pet trade) click this link:

Curtipes. Excellent frogger......He has

an email address there, and can help you with specifics that help the frogs retain genetic specifity. You can purchase pure curtipes here: aquaticfrogs.com To learn even more about these cute little water dancers, visit Amphibiaweb

If Dwarf pipids are your cup of tea, visit a website created by Brandon Ballengee, who is currently trying to breed/preserve

a pure strain of Hymenochirus curtipes (1 of 2 dwarf pipid species offered in pet trade) click this link:

Curtipes. Excellent frogger......He has

an email address there, and can help you with specifics that help the frogs retain genetic specifity. You can purchase pure curtipes here: aquaticfrogs.com To learn even more about these cute little water dancers, visit Amphibiaweb

Breeding Litorias

If Aussies (as I call them) are your passion∼also known as White's treefrogs, try Marcus Billings website. His years of success and interesting approaches can be of much benefit to the beginning Litoria breeder.

Breeding Red-Eyed Treefrogs

I breed

Red-Eyed treefrogs using a combination of two different strategies

by two different Online breeders of these frogs. I only vary with design of chamber, plant materials...and this difference will not change your success, as both methods these gentlemen describe work very well. Links to their appropriate methods are included here.

Read them both and you'll get an idea of how to start breeding your own

red eyed treefrogs.

Red-Eyed treefrogs using a combination of two different strategies

by two different Online breeders of these frogs. I only vary with design of chamber, plant materials...and this difference will not change your success, as both methods these gentlemen describe work very well. Links to their appropriate methods are included here.

Read them both and you'll get an idea of how to start breeding your own

red eyed treefrogs.

When I have the time, I will assemble my journal on my dealings in their breeding care, and have my webmaster load it up. In the meantime, here are those links:

Basic Breeding of Redeyes.pdf. Excellent research by this gentleman has lead to perfect results in breeding Red eyes. Check it out.

And try:

Monkeyfrogs.com. Another successful breeder with many great tips and precise

information to help you.

Try a flat of

Try a flat of

dichondra or

dichondra or

selaginella fern for a ground cover in the Rainchamber. After the Rain Chamber is no longer in use, you can transfer

the ground cover to the froglets new vivariums.

selaginella fern for a ground cover in the Rainchamber. After the Rain Chamber is no longer in use, you can transfer

the ground cover to the froglets new vivariums.